Outdoor Links

Hike Arizona

Trip Planning Guide

Trip Report Index

Calendar of Events

Library

Flagstaff

October 4, 1997

by Jeff Cook

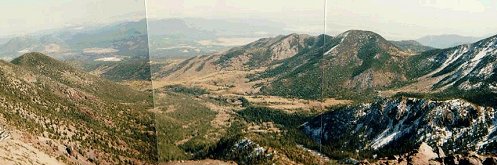

Inner Basin from Agassiz Saddle. |

|

This hike occurred later in the season than expected due to a longer than usual monsoon season. Nonetheless, weather conditions were excellent. The hike started at 4:30 AM in Gilbert, the 150-mile hike to the Snowbowl ski lodge quickened somewhat by the clever use of an automobile. We reached the trailhead around 9:00 AM; even at this relatively late time, there were still only about ten cars in the big dirt lot. It was me and my wife this time; her first time, and the first real exercise she tried to do after having a baby three months earlier. After stretching out a little from the 4-hour car ride, we hit the trail. The trail immediately crosses a ski slope, passing beneath the shorter of the resort’s two lifts. The shallow slope is pockmarked with the burrows of various small animals, and crossed in several places by old lift cables, which now stretch for unseen hundreds of feet through the coarse grass. Watch your step! The trail then enters the woods, from which it will not emerge for nearly another three miles. Aspen, Douglas Fir, and other varieties tower over your head in this old-forest section of the woods. The underbrush is thin, though there are quite a few saplings struggling upward through the shade. They are outnumbered, however, by the lanky, rotting trunks of fallen trees. The area is clearly in the early stages of breakdown. The trail is generally a gentle uphill grade for a while, with plenty of roots and half-buried rocks to test the fit of your boots. I wore ordinary running shoes for the first two miles, in hopes of staving off the almost inevitable blister. This practice justified itself less than a mile into the hike, when my wife had to turn back due to large blisters on both heels; her skin had become somewhat tender after several months without exercise! I would go the rest of the way alone, as I had two years earlier. Make sure your boots are well broken-in before making a hike like this, and always bring several pairs of socks! After less than a mile, this lower section of the trail meets up with the shorter path leading back to the ski lodge. There is a sign pointing hikers to the peak trail to the left, and some sign-in sheets in a metal box. The thoughtful hiker might bring along some fresh paper, as the sheets in the box are usually dense with signatures and marginally witty commentary right to every edge of every sheet. The trail continues to climb gradually through the forest, in a series of very long switchbacks, occasionally crossing impressive washes cutting steeply through the sides of the mountain. The first switchback is at the lower end of a long rockslide just over 10,000 feet. The third and fifth switchbacks return to the slide at 10,500 and 11,200 feet. By this time, I had encountered numerous icy spots despite the late date and the fact that the temperature was actually rising as I climbed higher. Starting around 40° at the trailhead, it maxed out in the high 50's at about 10,800 feet, at which height a moderate haze stretched across the plain from several nearby brush fires. As the trail approaches 11,000 feet (two and a half miles into the hike), one realizes that the trees have begun to thin out considerably, and are much smaller than they were lower down the slopes. At 11,400 feet, the trail winds around onto the sunny southeast exposure of the deep, half-mile-wide chute through which the Snowbowl’s numerous ski runs weave. The view of Agassiz Peak through the trees is imposing, and is a sobering reminder of how much of a climb is still ahead. It has been a long struggle already against the thinning atmosphere, and I probably made a good twenty rest stops to allow my lungs to replenish my blood oxygen levels before continuing. On top of that, I was slowed slightly by an annoying arthritis-like pain in my right hip; whether from altitude or distance, I ’m not sure. The trail now turns rather steeply uphill, the switchbacks becoming much shorter as it heads more or less directly for the lowest point of the saddle between Agassiz and Humphrey’s. The packed soil and its imbedded rocks have largely given way to coarse gravel and small rocks, and the footing is occasionally loose. The trees have also become dwarf fir and spruce, their heights trickling off to a dozen feet and less. Finally, close to what appears to be a diffuse tree line at 11,800 feet, you’re on the saddle. This is where you get your first view of the inner basin, the lush, sloping valley enclosed by the ring of peaks forming the San Francisco Mountains. From here, towering over the left side of the basin, you can also see Humphrey’s Peak for the first time. To the right, Agassiz points skyward. The view from the saddle is indescribable, and so I’ll leave it to the reader to check out the pictures. The saddle is also where many people turn back, discouraged by the sight of Humphrey’s Peak still a mile away and over 800 feet higher in elevation. It’s a good time to crash out and have a nice long lunch, provided you got an early enough start to make it to the top before the usual afternoon thunderstorms build up. On this occasion, there was not a single cloud in the sky, so I could sit and regain my energy for a while before the brisk wind that’s always present up there started biting through my clothing. The trail becomes somewhat indistinct above the saddle, but is not hard to follow, particularly since there are usually other hikers in view in both directions when the weather’s good. It’s all talus up here, a dark reddish-brown, porous rock that belies the mountain’s volcanic origin. The trail skirts around the outer slope of the long ridge as it arches upward and toward the North. The half-mile climb up the side of the ridge seems unbearably long and exhausting, but after a few false peaks, you finally find yourself a quarter mile away from the summit. The trail levels off a bit until the last 200 yards, allowing you to catch your breath before the final rocky stretch. On the summit, the Forest Service and other hikers have over the years erected a small enclosure, about 3 feet high and open on the north side, using rocks from the summit area. It’s a convenient windbreak, and also provides a more or less level place to sit. There are always other hikers on the summit, so there’s always someone to take your picture and people to ask the same of you. Rest for as long as the weather and the chilly wind will allow; just make sure you leave in time to get back down before dark! There’s another metal box up here, chained to a pole right at the north side of the enclosure. Sign in here, too, if there is any blank paper. Again, next time I go up I plan to bring some blank paper with me. |

The last quarter mile. The nearness of the summit and the fact that the trail is not as steep here make this part much easier than the previous mile! |

|

The hike up took me just over 4 hours. I spent just under an hour on top, taking pictures, resting, and enjoying the view. To the north is the canyon’s North rim. Continuing clockwise, the inner basin stretches down and away to the northeast; to the East is rounded Doyle Peak (11,460'), with Sunset Crater a few miles behind it. Then there’s the pointed Fremont Peak (11,969'), and Agassiz (12,350') is almost due south. To the southwest and west is the western plain toward Williams, with an excellent bird’s-eye view of Kendrick Peak. The view was very different this time from the first time I’d been there; the Aspen far below in all directions were a brilliant yellow, and the pale green of fields of grass contrasted sharply with the deep green of the surrounding evergreen forests. Contrast this with the lush green visible everywhere in the panorama included with the description for my 1995 hike. The view this time was also rather washed out, unfortunately, thanks to those nearby brush fires already mentioned. Heading back down again, you notice the steepness of the mountain’s slopes, plunging downward at nearly a 40° angle to the densely forested sections a thousand feet below, two thousand feet in the case of the rock slide which is directly below when you climb over the slight rise to the outer slope of the ridge. It makes you think carefully about each step down on the often loose talus. I was also slowed somewhat by the pain in my right hip, which had me hobbling around the summit like an old man once I had rested for long enough for it to stiffen up. Back at the saddle, I rested for about 20 minutes, mostly to change my socks. The feeling of fresh, cool, dry air on one’s aching feet is quite refreshing! From the saddle you can just see the trailhead and parking lot a mile and a half down the ski slope. The resulting feeling of isolation is an excellent set-up for what tends to be a very gloomy and dispiriting descent. Going down the footing is slippery, at first because of the gravel and then because the trail through the woods is often muddy due to late season runoff. The last two or three miles down is best done with the brain and the legs in automatic, watching carefully for roots, rocks, and muddy spots, of course, but trying not to give in the rubbery exhaustion of your back and legs, or think about how much further you have to go through the relatively murky and seemingly endless forest. Already by this time I could feel the swelling in my knees and hips. On the way down I passed an almost endless stream of people on their way up, every one of who asked how much further it was to the top. As I got closer to the bottom, my responses gradually went from “another mile and a half, don’t give up now” to “forget it, you won’t get halfway before dark.” Finally you reach the last switchback at the bottom of the rockslide, having passed Snow Bowl Ski Lodge 1 Mile sign a bit further back, and hope again returns that you’ll soon be back in the comfort of your car where you can swear never to hike this mountain again. At the fork, you can either take the short route to the ski lodge for some food and drink (if it’s open), or the long route directly back to the lower parking lot. I took the short route this time, figuring on finding my wife milling about in the afternoon crowds. It had taken me two and a half hours to get back down, with no rests between the saddle and the ski lodge. I eventually found my wife, and as I expected she had taken the chairlift up to the 11,600-foot level on Agassiz. It’s a very nice ride, and a good way to get a great view without much exertion. On the way home, I remembered the first time I hiked Humphrey’s two years earlier. I had sworn never to do it again. This time I was a little more lenient; I swore never to do it more than once a year. By the time I got home I could barely haul myself up the stairs, my knees and hips ached so much. But after a few days, I reached the conclusion I knew I would: the experience of standing on the top of Arizona is well worth the effort and the discomfort! I can’t wait for Mt. Whitney this fall! |

Top of Page

Top of Page

Arizona Trailblazers Hiking Club, Phoenix, Arizona

Comments? Send them to the AZHC .

updated August 12, 2020